PARTNERS/PROJECTS:

- Pathfinder,Continuum of Care for Post-Partum Hemorrhage Project in India and Nigeria Pathfinder Continuum of Care Project

- HDI, Niger Postpartum Hemorrhage Project

- JSI, East Timor (Timor Leste): JSI Timor Continuum of Care Project

- Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania: Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania (Improving community to health facility delivery, and Maternal Death in Southern Tanzania

- Clinton Health Access Initiative, Ethiopia, Tanzania: Household to Hospital Continuum of Care Project Ethiopia:

- URC MATERNAL HEALTH PROJECT, Cambodia

What is the Continuum of Care for PPH?

The United Nations Millennium Development Goal 5A aims to reduce maternal mortality by 75% by 2015, but few countries will reach that goal. Although maternal mortality has declined substantially over the past decade, 273,500 maternal deaths occurred in 2011, 99% of those in low-resource countries. The most common cause of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity in these countries is postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).

A series of delays contribute to the late receipt of definite PPH care and PPH-related death in low-resource countries including:

1) Delay in problem recognition, including an inability to accurately quantify the amount of blood loss;

2) Delay in deciding to seek assistance from skilled obstetric care providers;

3) Delay in reaching a facility that can provide lifesaving treatment; and

4) Delay at that facility in the receipt of definitive emergency obstetric care.

Intrinsic to these delays are system-level factors including inadequate numbers of skilled health care providers, lack of and/or improper storage of uterotonics, poor adherence to active management of the third stage of labor, underestimation of blood loss, and, finally, deficiencies in the communication and transportation infrastructure which impedes efficient transfer to higher levels of care. Each of these delays drastically increases risk of mortality for women experiencing PPH. These must be overcome at the community and system levels to reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality from PPH in low-resource settings. In order to effectively promote safer motherhood, a continuum of care (CC) approach to pregnancy and delivery must be implemented. The continuum of care model is a multifaceted solution that addresses gender, medical, social and systematic factors that lead to preventable and unnecessary maternal deaths. The continuum of care approach incorporates multiple strategies for the prevention, recognition, and management of postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings through six key components.

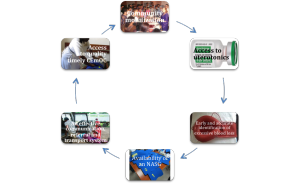

The components of this model are:

1) Community mobilization

2) Routine use of prophylactic uterotonics and availability of treatment uterotonics

3) Early and accurate identification of excessive blood loss

4) Availability of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG)

5) An effective system of communication, referral, and transport to a higher-level care facility

6) Access to quality, appropriate, and timely comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEmOC)

Community Mobilization

In order to effectively combat preventable maternal death and morbidity, communities must be aware of the four delays and the health interventions that can prevent and treat PPH. Through developing an ongoing dialogue between community members about their health and empowering communities to take action on its own health needs, a sustainable and successful community-based health intervention is possible. Working in partnership with the community health care system by building upon existing assets and resources, and collaboratively evaluating a locally appropriate response to community health needs, interventionists can gain and maintain the trust of community members and institute effective and sustainable maternal health care system changes.

Additionally, raising awareness about PPH can promote an understanding of the existing barriers faced in accessing CEmOC (comprehensive emergency obstetric care) and encourage the community to identify strategies to overcome these barriers in order to improve maternal health outcomes. For example, by developing a birth and complication readiness plan, a community can address the first three delays by recognizing the problem, deciding to seek care, and reaching the facility. When community members and health facilities work together, a community transport plan can be developed within each neighborhood and village so families are prepared to transport to a skilled referral facility when emergencies arise.

Uterotonics for Prophylaxis and Treatment

Routine postpartum administration of an uterotonic is the next component of the CC for PPH model. Oxytocin, IM or IV, is the drug of choice for prophylaxis. However, in many settings oxytocin is not often available at the community level because it requires skilled attendants for administration, cold storage, and sterile injection equipment. Therefore, WHO, FIGO, and ICM have suggested the use of misoprostol where oxytocin is unavailable or in the absence of the active management of the third stage of labor. For women who continue to bleed despite prophylaxis, uterotonics for treatment must also be available.

Accurate Assessment of Blood Loss

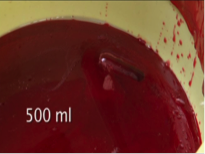

Even among skilled health care providers, visual estimation of blood loss is notoriously underestimated. Family members and unskilled birth attendants are believed to recognize the signs of excessive bleeding during labor and postpartum only 11% of the time. If a woman bleeds more than 500 ml, she may need immediate attention or referral for treatment at a higher-level facility. To respond to the delay in problem recognition, community-based health care providers and family members need to be able to recognize the danger signs of excessive bleeding. Information and education programs can help with recognition of danger. Further, use of a reliable blood loss detection method can help birth attendants to rapidly recognize excessive bleeding instead of waiting for changes in vital signs (blood pressure, pulse and pallor) and/or unconsciousness. There are several valid options for timely and accurate assessment of PPH in low-resource settings:

At the Facility Level

Methods for Identifying Blood Loss

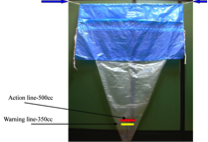

The BRASSS-V blood collection drape

The BRASSS-V blood collection drape

- Yellow line indicates alert level of blood loss

- Red line indicates action is needed

For family members and community health workers, accessing facility-level blood measuring tools is not possible. Being able to measure blood loss precisely is critical to recognizing when a woman is hemorrhaging and therefore reducing delays in referral to a higher-level facility.

Research shows that there are many local materials that can be used to effectively measure blood loss at the community level of PPH care. Some of the materials and methods for blood loss measurement are highlighted below:

Local Materials (kangas, saris, duppata, etc.)

Local Materials (kangas, saris, duppata, etc.)

Researchers in Tanzania learned in a focus group with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) that local materials are used to measure postpartum blood loss. In Tanzania, the kanga is a rectangular, standardized (100 cm x 155 cm) cotton-only fabric that is locally produced and sold, used by African women for various purposes. TBAs in Tanzania use old kangas as a postpartum blood loss measurement tool. Researchers verified that two kangas soaked with blood represented slightly more than 500 ml; thus guiding TBAs that intervention is necessary after two kangas are saturated. There are kanga-type garments in many different cultures (e.g., sari, dupatta, sarong), and the kanga method can be adapted to other standardized clothes or manufactured absorbent pads in different regions. Maternal health providers and advocates should verify that the cloths are sold at a standardized size and measure the number of garments or pads required to absorb 500 ml of liquid.

The blood mat was developed by Dr. Abdul Quaiyum, a researcher at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh (ICDDR,B). It is a 20 inches x 20 inches biodegradable mat composed of cotton layers and backed by plastic that can absorb a total of 500 ml of fluid. It has been used by families and community health workers to identify hemorrhage in women giving birth at home. The mat is placed under a mother immediately after birth. If the mat stops absorbing blood, it indicates that the woman is hemorrhaging and should be immediately referred to a facility.

Equipping families and community health providers with the tools to validly assess blood loss can allow for earlier detection of PPH and more prompt action to provide medical intervention and/or transfer the woman to a higher-level facility.

Hypovolemic Shock

A delay in diagnosis and treatment of continued blood loss combined with underestimation may quickly escalate to hypovolemic shock, cardiopulmonary arrest, and death. Even despite primary prophylaxis and early detection of PPH, a woman may continue to bleed and progress into hypovolemic shock. The non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG), the fourth component of the CC-PPH model, is a first-aid tool used to stabilize women in shock until they can reach a CEmOC facility capable of providing definitive PPH treatments.

Non-pneumatic Anti-shock Garment (NASG)

The NASG addresses the delay in reaching a higher-level facility by stabilizing women during transport and when waiting for treatment. The NASG is a lightweight, inexpensive, reusable device that decreases blood loss and reverses shock. When the NASG is applied in a community facility or at home, it can improve circulation to the core organs and decrease bleeding while the woman is awaiting transport, being transported, or during delays in receiving care at higher-level facilities. The NASG is not a treatment for PPH, but it can be used to buy time to obtain definitive treatment. Family members, traditional birth attendants, community health workers, rural auxiliary nurses, and even ambulance or conveyance drivers can be quickly and easily trained (Safe Motherhood Training Video) to apply the NASG tightly enough to improve the woman’s status without causing harm. The NASG can be worn over clothing, no inflation is required, and it can be re-used at least 70 times. It has been shown to be a cost-effective or cost-savings device.

Addressing Barriers to Communication and Transportation

The delays experienced between community health centers to higher-level care facilities are often fatal to women experiencing PPH and hypovolemic shock. Spatial barriers, such as distance or rough terrain or weather-related obstacles, can pose significant challenges to referring patients with PPH to CEmOC facilities in a timely manner. Problems related to communication with skilled providers may also inhibit a prompt referral. Minimizing these delays is critical to saving mothers’ lives; many low-resource countries have implemented innovative strategies for limiting delays in transportation and communication to higher-level facilities.

Once a woman with PPH arrives at the skilled care facility, health care providers must be trained and equipped to respond to a CEmOC emergency quickly and effectively.

Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care (CEmOC)

The final phase of the CC-PPH model addresses the delay at the facility in providing timely, quality, definitive emergency treatment. Unfortunately, there is a lack of skilled attendants and women often face long delays at the facility level before receiving the medications, IV fluids, blood transfusions and surgeries they may require. Barriers to quality care in low-resource settings include overburdened health facilities, shortages of physicians and nurses, poor retention of skilled personnel, lack of operating theaters and surgical equipment, drug shortages, poor sanitation, hospital fees, and limited blood supplies. Ministries of health, donors, NGOs and others working in reproductive health need to prioritize improvements in quality of care at all facilities.

CONCLUSION

The high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity in low-resource settings are associated with institutional, environmental, cultural, financial, and social barriers to providing skilled care and to preventing, recognizing and managing PPH. No single intervention can prevent maternal mortality and morbidity, but a multifaceted, systematic, and contextualized PPH Continuum of Care approach that address all factors directly contributing to maternal death from hemorrhage is essential if progress is to be made in this area. Commitment and support from key stakeholders, government organizations and policymakers will ensure the feasibility and sustainability of evidence-based interventions, including universal prophylactic uterotonic administration, a valid blood measurement tool, and the NASG.

Safe Motherhood Continuum of Care Projects with Global NGO and GO Partners:

Tanzania, IHI and MOH

In November, the UCSF Safe Motherhood team arrived in Tanzania to launch the Ifakara Health Institute’s Lifewrap intervention. Across eight rural districts, 278 health facilities are being trained to use the Lifewrap with the first woman saved just days after the

introduction.

As the Ifakara training team was still on the road, heading home from training and equipping the sites, they received a phone call from the newly trained hospital hospital. Seleman Mbuyita, the team leader

reported:

“A woman’s life has been saved. Kahama hospital received a referral case of a woman from the health center with placenta previa who had turned paper white but Lifewrap came to rescue! The woman rests in post op ward in a sound condition. What can be more rewarding than this. I was feeling very exhausted but suddenly I am rejuvenated!”

All participating sites will be trained by March 2015 and monitored by the Safe Motherhood team until October 2016.

Nigeria & India, Pathfinder International

A Continuum of Care for PPH Project was conducted with Pathfinder International India and Nigeria (2007-2012). The project was started in 5 states in Nigeria, which later was scaled up to 12, and 4 states in India. The aims were to reduce maternal deaths through educating the local community and birth assistants in methods to prevent complications of childbirth and early identification of problems; setting up communication systems, providing referrals and transport for women who need treatment from health care facilities, provision of and training on NASGs, and ensuring rapid, evidence-based treatment is available at the health care facilities.

The NASG is an essential part of this continuum for women who suffer excessive bleeding and shock despite prevention and early recognition.

For more information please visit Pathfinder, (Pathfinder Continuum of Care Project ) or you can read the publication co-authored by Dr. Miller. You can also read about the Continuum of Care in 2 publications co-authored by Dr. Miller: A Continuum of Care Model for Postpartum Hemorrhage in the International Journal of Fertility & Women’s Medicine 52(2-3), 97-105, 2007 and A Community-Based Continuum of Care Model for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage in Low Resource Settings. Kapungu, CT; Koch, A; Miller, S; Geller, SE. Pg 555-561., Chapter 67 in 2012, FIGO 2nd Edition, PPH Textbook.

Agra, India, Rainbow Hospital

The UCSF NASG Team presented at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Association Meeting in the new Rainbow Hospital referral center in Agra India on June 5th 2013. The interactive talks included enthusiastic interactions by local maternal health advocates and hospital staff: Overview of Postpartum Hemorrhage, Blood Loss Estimation and Demonstration, and Overview of the NASG with Demonstration. Kind thanks to Dr. Narendra Malhotra for organizing this exciting event. Dr. Malhotra began implementing the NASG in hospitals that night. By December 2014 the peripheral clinics and ambulances are using NASG before sending to Rainbow Hospital, and the staff and Dr. Malhotra believe it is contributing to decreasing maternal mortality from hemorrhage. Dr. Malhotra posts success stories on the NASG on his Rainbow Hospital Facebook Page.

URC and MOH: Cambodia, Better Health Services Project

http://www.urc-chs.com/project?ProjectID=6

The NASG was introduced in Cambodia by Jerker Liljestrand of URC Better Health Services in 2012 as part of the Improving Maternal Health Project. Professor Miller traveled to Cambodia and trained health workers and MOH maternal health experts on NASG and it’s place in a Continuum of Care for PPH. Dr. Liljestrand reported that by December 2014 at a National EmONC workshop in Cambodia, the NASG was a hot topic. Demand is now increasing for nation-wide implementation. Users say that having the NASG is empowering for the health center midwives; they now know there is something they can do to save a mother’s life.

Dr. Liljestrand also noted that there is also an interesting “red flag effect” where the red (burgundy, size small) NASG acts as a red flag. Once it has been applied at the health center, everyone knows that you must send the woman to a referral hospital at once, and at the referral hospital any woman who arrives wearing the NASG is “wearing” a red flag requiring urgent care.

HDI and MOH, Niger: Postpartum Hemorrhage Project (Initiative to Prevent Women from Bleeding to Death at Childbirth)

Working with FIGO, HDI ex. Dir Dr. Anders Siem and Dr. Zeidou Alassoom, Safe Motherhood Program staff Elizabeth Butrick traveled to Niger in 2013. HDI has collaborated with Government of Niger to rapidly achieve MDGs 4 and 5 on a public health scale, and on rapid community-based prevention of obstetric fistula since 2008. Beginning in late 2013, Government of Niger and HDI are collaborating on a nationwide Initiative to Prevent Women from Bleeding to Death at Childbirth, using misoprostol for prevention, and ballon tamponade and NASG for rescue treatment. By 2014 Niger competed distribution of supplies and training to the last level of the cascade in the final districts, and the Initiative to Prevent Women from Bleeding to Death at Childbirth is now under way in all of the country’s eight Regions.

CHAI Ethiopia: Household to Hospital Continuum of Care Project Ethiopia:

With consultation with UCSF’s Safe Motherhood Team and direct training by our colleagues from Pathfinder and Nigeria, Ibadan UCH, CHAI Ethiopia embarked on a pilot NASG project in 2011. They began their pilot in 2012 in 9 hospitals, 4 in Tigray and 5 in Oromia. Results comparing rate of mortality from PPH from baseline to endline, 14.2% (27/190) vs. 2.9% (5/170). Women were 80% less likely to die from PPH after the NASG was introduced. The NASG has now been scaled up to nearly all districts in Ethiopia.

For an in-depth look at the NASG and its uses, visit our webpage: www.safemotherhood.ucsf.edu/nasg.

Recent Comments